This sample Claude Levi-Strauss Essay is published for informational purposes only. Free essays and research papers, are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality essay at affordable price please use our custom essay writing service.

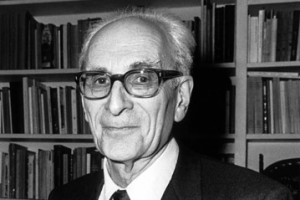

Few anthropologists have acquired in their lifetime the international fame and audience of Claude Levi-Strauss. Since the end of World War II his ideas have taken hold throughout the human sciences. Although his work is not easily accessible to the uninitiated (Leach 1970), nor have all been convinced by his propositions — far from it — he has radically transformed the way anthropologists pose questions and define their object in central areas like kinship, classification and mythology. In advocating an approach inspired by structural linguistics, his work has brought about an epistemological break with previous methods of analysis. We can thus refer to a period ‘before Levi-Strauss’ and one ‘after Levi-Strauss’.

This is all the more remarkable since, like most of his French contemporaries, he was self-taught as an anthropologist, having received his academic training in philosophy and law (at a time when only a few of the major British and American universities were offering programs in anthropology). Nevertheless, we must not overlook the fact that he has always paid homage to his predecessors (Mauss, Boas, Lowie, and Radcliffe-Brown, among others) whether or not he agreed with them. On the other hand, he has not hesitated to engage in controversy with philosophers, who have taken him to task on a number of occasions. No one who reads his work is left indifferent and he has contributed much to anthropology’s reputation in the human sciences.

From the aesthetic to the sensual

Levi-Strauss has been described as sensitive, dignified and reserved, someone who has always privileged rigorousness in his professional life, and no doubt striven, as a result, to maintain a certain distance from events, people and facts. In order to know more about him we can turn to his own testimony (Charbonnier 1969 [1961]; Levi-Strauss 1983 [1975, 1979]; Levi-Strauss and Eribon 1991 [1988]), concerning his roots and intellectual development, and relate certain aspects of his work to his life and personality.

Levi-Strauss has been described as sensitive, dignified and reserved, someone who has always privileged rigorousness in his professional life, and no doubt striven, as a result, to maintain a certain distance from events, people and facts. In order to know more about him we can turn to his own testimony (Charbonnier 1969 [1961]; Levi-Strauss 1983 [1975, 1979]; Levi-Strauss and Eribon 1991 [1988]), concerning his roots and intellectual development, and relate certain aspects of his work to his life and personality.

Those close to him all agree on his distinctive sensibility, which leads him sometimes to prefer the company of nature, rocks, plants and animals, to that of people. Undoubtedly this is the key to his aesthetic sensitivity, whether in relation to painting, music, poetry or simply a beautiful ethnographic object (Levi-Strauss 1998 [1993]). Is this aesthetic refinement part of his family heritage? This is quite plausible when one takes into consideration that his great-grandfather was both a composer and a conductor, that two of his uncles were painters, as was his father who was also passionately interested in both music and literature. This aesthetic sense can be found in most of Levi-Strauss’s topics; it is expressed in the choice of titles, in the choice of images (on the covers of the French editions of Mythologiques, or The Savage Mind, even in the colors of the characters of the titles (e.g. the raw, green and red; the cooked, brown), and the organization of the contents (e.g. the musical arrangement of Mythologiques beginning with The Raw and the Cooked, which is devoted to music, and concluding with the ‘finale’ of The Naked Man).

In his remarkable autobiographical volume, Tristes Tropiques (Levi-Strauss 1976 [1955]) he wrote about his early interest in nature and a taste for geology which led him to scour the French countryside in search of the hidden meaning of landscapes. We can add to this youthful fascination a close reading of Freud and a discovery of Marxism. Although each operates on a different level, he tells us that these three approaches (geology, Marxism and psychoanalysis), show that true reality is never that which is the most manifest, and that the process of understanding involves reducing one type of reality to another. For each, he adds, the same problem arises, that of the relationship between the sensory and the rational; and the objective of each is a kind of super-rationalism which can integrate the sensory and the rational without sacrificing any of the properties of either. Although he has distanced himself gradually from Marxism and pschoanalysis, this is nevertheless the program that Levi-Strauss has striven to realize throughout his work.

From the view from afar to the discovery of the other

Levi-Strauss has the qualities required to carry out this program, particularly a distinct taste for formal logic and an exceptional memory, both reinforced by a solid academic training. Yet it is his two long periods of residence outside France in the New World — more than ten years altogether — which have most determined the orientation of his scientific life and work. The first period began in 1934 when, as a young twenty-six year-old teacher of philosophy, he received an offer from one of his former teachers to go and teach sociology at the University of Sao Paulo. His reading of Robert Lowie’s Primitive Society had already filled him with a desire to exchange the closed, bookish world of philosophical reflection for that of ethnographic work and the immense field of anthropology. He stayed in Brazil until 1939, gaining the opportunity to make contact with the Amerindian cultures which occupy such an important place in his work. At the end of his first academic year at Sao Paulo he spent several months in the Matto Grosso among the Caduveo and the Bororo — his baptism into the world of ethnography — and published his first article on Bororo social organization. In 1938 he carried out a new expedition, this time among the Nambikwara, a relatively unknown group, whose social and family life he subsequently described in a monograph.

After returning to France in 1939, he was compelled by the war to leave once again. This time he went to the United States where in 1941 he was offered a new teaching post at the New School for Social Research, moving in 1942 to New York’s Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes. His stay in New York lasted until 1947, including three years as cultural adviser to the French Embassy. This was an opportunity for him to familiarize himself with American anthropology and to have access to a wide range of anglophone ethnography which he used for his doctoral thesis The Elementary Structures of Kinship (Levi-Strauss 1969 [1949]). During this period he met many eminent European intellectuals who like himself had come to North America as refugees, amongst them the linguist Roman Jakobson, who introduced him to structural linguistics and exerted a decisive influence on his thinking.

His final return to France marked the beginning of a brilliant and prolific academic career which took him to the College de France (1958, Chair in Social Anthropology), after the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique, the Musee de l’Homme (1948) and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (1950, Department of Religious Studies), where he was elected to the chair of Comparative Religions of Pre-Literate Peoples, a post once held by Marcel Mauss. He has received the highest national and international honors, including election in 1973 to the Academie Frangaise. He has produced more than twenty books (translated into most of the major languages of the world) in this forty-five year period, continuing well after his retirement from the College de France in 1982. Under his impetus, and that of the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale which he created in 1960, French anthropology has gone through a period of great development and its influence has spread throughout Europe and the rest of the world.

A theory of kinship based on alliance

Far from confining himself to the data he had gathered in South America or to the problems that were preoccupying his North American colleagues, Levi-Strauss tackled, in his first major theoretical work (Levi-Strauss 1969 [1949]), one of the most ambitious anthropological projects of the period, the unification of the theoretical field of kinship; a field dominated for half a century by British anthropology. Reversing the prevalent perspective of the time which considered relations of descent as the key to kinship systems, Levi-Strauss based his theory of kinship on relationships of marital alliance, showing that the exchange of people as spouses is the positive counterpart to the incest prohibition. This is founded on reciprocity, in Mauss’s sense of the term (in his essay on The Gift), and the relationships associated with it are the binding force of the social fabric. Levi-Strauss showed that the rules that regulate these relations and the structures that express them can be reduced to a small number. He even suggested an analogy between the exchange of goods (after Mauss), the exchange of messages (after structural linguistics) and the exchange of women between groups. The question remained, however, of whether these ‘structures’ were a reflection of social reality, or were instead to be traced back to the properties of human thought. He returned to settle this question in his other major work, the four volumes of Mythologiques. He had intended to follow The Elementary Structures of Kinship, which dealt with societies in which the choice of spouse is prescribed and restricted to one particular category of kin (so-called felementary structures), with another work devoted to f complex structures of kinship. But, except for several courses and lectures in the years immediately prior to his retirement, and his development of the idea of societes-a-maison (house-based societies), this project has never been realized.

From primitive thought to mythical thought

In 1950 Levi-Strauss was elected to a chair of Comparative Religions which led him to put kinship temporarily to one side in order to devote himself, and his structural method, to mythology and indigenous classifications. First of all, he deconstructed the concept of totemism (Levi-Strauss 1963a [1962]). In the evolutionary perspective that prevailed at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, totemism had been considered as one of the first forms of primitive religion, in which human groups identified themselves with animal or plant species. Several British anthropologists (Fortes, R. Firth, Radcliffe-Brown and Evans-Pritchard) had tried to reinterpret totemism in the light of their own ethnographic data, but had failed to reach the level of logical abstraction to which Levi-Strauss raised the debate. For Levi-Strauss, totemism is a system of classification of social groups based on the analogy with distinctions between species in the natural world. The relationship between the individual animal and the species as a whole provides a natural intellectual model for the relationship between a person and a broader social category; animals were not made totems because, as Malinowski had claimed, they were ‘good to eat’, but because, in Levi-Strauss’s phrase, they were ‘good to think’.

Levi-Strauss went further in The Savage Mind, originally published in the same year (1966 [1962]), in which he demolished the evolutionist idea of a prelogical stage of primitive thought. The French title, La pensee sauvage, involves an untranslatable pun — it means both ‘wild pansies’ and ‘savage thought’. This type of thought is, according to Levi-Strauss, logical, but non-domesticated, natural, and wild. Close to sensory intuition, it operates by working directly through perception and imagination. It is universal and manifests itself both in art and popular beliefs and traditions.

The Mythologiques (four volumes published between 1964 and 1971) developed the line of enquiry initiated in these two books since ‘mythical thought’ is a product of ‘primitive thought’. These volumes constitute Levi-Strauss’s most important work, not only because of their innovative approach to the field, but also because of their immense scope (close to a thousand myths taken from 200 Amerindian groups), their size, and the duration and intensity of their author’s intellectual investment. To these we can add three later works which also deal with mythology: The Way of the Masks (1983 [1975, 1979]), The Jealous Potter (1988 [1985]) and The Story of Lynx (1995 [1991]).

In focusing on material from the two Americas where he spent ten years of his life, Levi-Strauss not only returned to the site of his first anthropological studies but also drew on his firsthand knowledge of the natural environment of several of the groups studied, as well as the rich ethnographic literature housed in the great libraries of New York. With these he refined his structural method and showed that the structures of myths could be traced back to the structures of human thought. No longer was there any uncertainty about the possible effect of social constraints on structure: he stressed that mythology does not have an obvious practical function, and that myths function as systems of transformations. Through analysis he was able to describe their workings in terms of relations of opposition, inversion, symmetry, substitution and permutation.

He broke new ground by superimposing on the “diachronic order of the narrative, which expresses itself in “syntagmatic relations between elements, a synchronic and paradigmatic order between groups of relations. He also innovated by defining myth as the summation of its variations, no one being more true than the others. By a series of analogical substitutions, the variations provide a logical mediation which resolves the contradictions found in the myth. In other words, within a given myth we can compare elements and recurring relationships which might be obscured by concentrating on the narrative thread alone; and we can elucidate these relationships by looking at other related myths, from the same culture or from neighbouring peoples, in which variations on these relationships recur. These variations and their mediating function constitute a group of transformations, the logic of which has been represented by what Lévi-Strauss refers to as the canonical formula:

Fx (a) : Fx (b) : : Fx (b) : Fa-l(y)

in which a and b are terms, and x and y functions of these terms. In The Jealous Potter, he clearly demonstrates the scope of this formula. If one replaces a by n (nightjar), b by w (woman), x by j (jealousy) and y by p (potter), this gives:

Fj (n) : Fp (w) : Fj (w) : Fn-1(p)

The function ‘jealousy’ of the nightjar is to the function ‘potter’ of the woman, what the function ‘jealousy’ of the woman is to the inverted function ‘nightjar’ of the potter. From the two known relationships nightjar/jealousy and jealousy/potter one can infer the relationship potter/nightjar (confirmed by other myths) the inversion of which allows the logical circle to be closed. Mythical thought, Levi-Strauss tells us, viewed from the perspective of logical operations, cannot be differentiated from practical thought; it differs only with respect to the nature of the things to which its operations apply.

For Levi-Strauss, then, anthropology must investigate the structures underlying the diversity of human cultures, structures which refer to the properties of the human mind and the symbolic functions which characterize it. This intellectualist approach to humans and human culture, which raises the logic of sensory qualities to the rank of scientific thought, has been acclaimed by some and denounced by others. Yet it constitutes one of the most stimulating and powerful theories in twentieth-century anthropology.

Bibliography:

- Boon, J. (1973) From Symbolism to Structuralism: Lévi-Strauss in a Literary Tradition, Oxford: Blackwell.

- Charbonnier, G. (1969 [1961]) Conversations with Claude Lévi-Strauss, London: Cape.

- Hayes, E.N. and T. Hayes (eds) (1970) Claude Lévi-Strauss: The Anthropologist as Hero, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hénaff, M. (1998) Claude Lévi-Strauss and the Making of Structural Anthropology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Leach, E. (1970) Lévi-Strauss, London: Fontana.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963 [1958]) Structural Anthropology, New York: Basic Books.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963a [1962]) Totemism, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966 [1962]) The Savage Mind, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969 [1949]) The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969 [1964]) The Raw and the Cooked (Mythologiques I), London: Cape.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1973 [1967]) From Honey to Ashes (Mythologiques II), London: Cape.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1976 [1955]) Tristes Tropiques, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1977 [1973]) Structural Anthropology II, London: Allen Lane.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1978 [1968]) The Origin of Table Manners (Mythologiques III), London: Cape.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1981 [1971]) The Naked Man (Mythologiques IV), London: Cape.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1983 [1975, 1979]) The Way of the Masks, London: Cape.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1988 [1985]) The Jealous Potter, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1995 [1991]) The Story of Lynx, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1998 [1993]) Look, Listen, Read, New York: Basic Books.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. and D. Eribon (1991 [1988]) Conversations with Claude Lévi-Strauss, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sperber, D. (1985) ‘Claude Lévi-Strauss Today’, in D. Sperber, On Anthropological Knowledge, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

See also:

- History of Anthropology Essay

- Anthropology Essay

- Anthropology Essay Topics

- Anthropology Research Paper

Free essays are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom essay, research paper, or term paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price. UniversalEssays is the best choice for those who seek help in essay writing or research paper writing in any field of study.