This sample Older Homeless Persons Essay is published for informational purposes only. Free essays and research papers, are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality essay at affordable price please use our custom essay writing service.

In the United States, older homeless persons—those age fifty and over—often seem invisible. Public policy generally focuses on younger homeless people or on social categories in which the aging are subsumed without special notice, such as disabled individuals and veterans.

For purposes of studying homeless populations, researchers have set the aging marker at anywhere from age forty to sixty-five. However, a growing consensus holds that the “older homeless” should be defined as age fifty and over. Indeed, at that age, many homeless persons look and act ten to twenty years older.

Although the proportion of older persons among the homeless has declined since the 1980s, their absolute number has grown. (As for the actual percentage of aging Americans who are homeless, estimates vary widely—from about 3 to 28 percent—due to heterodox methods and definitions of aged status.) In any case, the proportion of older homeless persons can be expected to increase dramatically as more baby boomers turn fifty. Thus, with an anticipated doubling of the fifty-and-over population by about 2030, a comparable increase in the number of older homeless persons is likely. The current low estimate of 60,000 would grow to 120,000, while the high estimate of 400,000 would mushroom to 800,000.

Factors Contributing To Homelessness In Older People

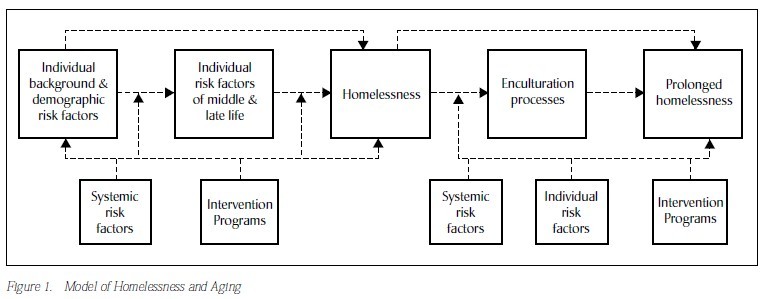

Homelessness generally results from a concurrence of conditions, events, and risk variables. The flow chart in Figure 1 depicts these factors in four categories, summarized below.

- Personal risk factors may accumulate over a lifetime. Except in the case of extremely vulnerable individuals, homelessness is likely to occur only when several of these personal risk factors coexist.

- Systemic factors play a critical role. In most instances, such variables as the availability of low-cost housing and the income to pay for it are the ultimate determinants of homelessness.

- Enculturation factors—that is, a person’s adaptation to the street or shelter—may further sustain and prolong homelessness.

- Programmatic factors can prevent or terminate homelessness, depending on the timeliness, quality, and availability of the service intervention.

Individual Risk Factors

The principal risk factors found to increase vulnerability to homelessness among older individuals are described below, based on studies conducted in the period from 1983 to 1998.

Figure 1. Model of Homelessness and Aging

Gender: The ratio of older homeless men to women is approximately 4:1.

Race: African-Americans are overrepresented among older homeless populations—and they are even more so among their younger counterparts.

Fifty to sixty-four age range: Because of the entitlements available to persons at age sixty-five, the risk of homelessness drops at that age. Indeed, the proportion of elders over sixty-five among the homeless is roughly one-fourth of their representation in the general population. Conversely, persons between fifty and sixty-four are overrepresented among the homeless, close to double their representation in the general population.

Extremely low income: Older homeless persons are likely to come from poor or near impoverished backgrounds and to spend their lives in similar economic status. More than three-fifths worked in unskilled or semi-skilled occupations. Median current income is roughly one-half the poverty level.

Disruptive events in youth: About one-fifth of older persons have had disruptive early life events such as the death of parents, placement in foster care, and so forth. Similar rates hold for younger homeless persons as well.

Prior imprisonment: Roughly half of older men and one-fourth of older women report prior incarceration.

Chemical abuse: Although the prevalence of alcoholism varies, older men have rates about two to four times higher than do older women, and older men have higher rates than their housed age peers. Illicit drug abuse falls off sharply in homeless persons over fifty, but this may increase with the aging of the younger generation of heavy drug users.

Psychiatric disorders: Levels of mental illness have been found to be consistently higher among women than men, with psychosis more common among women and depression equally prevalent, or slightly more prevalent among men. Studies in New York City have found that 9 percent of older men and 42 percent of older women displayed psychotic symptoms, whereas 37 percent of men and 30 percent of women exhibited clinical depression. Levels of cognitive impairment ranged from 10 to 25 percent, but severe impairment occurred in only 5 percent of older homeless persons, which is roughly comparable to the general population.

Physical health: Older persons suffer from physical symptoms at roughly 1.5 to 2 times the level of their age peers in the general population, although their functional impairment was no worse.

Victimization: Both younger and older homeless report high rates of victimization. Studies have found that nearly half of older persons had been robbed and one-fourth to one-third had been assaulted in the past year. One-fourth of older women reported having been raped during their lifetime.

Social supports: Social networks of older persons are smaller (about three-fourths the size of their age peers’) and more concentrated on staff members from agencies or institutions. They are more likely to involve material exchanges such as food, money, or health assistance; to entail more reciprocity; and to have fewer intimate ties. Although not utterly isolated, older homeless persons lack the diverse family ties that characterize their age peers in the general population. Only 1 to 7 percent are currently married, versus 54 percent among their age peers. Nevertheless, various studies have found that about one-third to three-fifths of older homeless persons believe that they could count on family members for support.

Prior history of homelessness: One of the key predictors of prolonged and subsequent homeless episodes is prior history of homelessness. Durations of homelessness are substantially higher among older men than older women.

Other Risk Factors

Once a person becomes homeless, evolution into long-term homelessness involves an enculturation process in which the individual learns to adapt and survive in the world of shelters or streets. Shelter life may foster this enculturation in several ways. First, “shelterization”—adapting to the group lifestyle and organization of homeless shelters—may replicate earlier military or prison experiences for some men, while others develop a type of “learned helplessness.” Second, shelters may be a rational choice based on safety and stability, especially for women. Third, they offer a new social support system; residents typically consider about one-third of their shelter or flophouse comrades to be “intimates.”

Furthermore, certain older persons (men, the mentally ill, and those with prior homeless episodes in particular) are more apt to remain homeless for extended periods, a trend most likely reflecting impediments at the personal and systemic levels. The two principal systemic factors that create homelessness are lack of income and lack of affordable housing. Even in cities with adequate housing supplies, it may be out of reach for the poor, because of poor-quality jobs, unemployment, and low incomes. Conversely, in cities where incomes may be higher and jobs are more plentiful, tight rental markets stemming from middle-class pressures and escalating living costs also make housing less available to lower-income persons. Both of these conditions can push some people over the edge into homelessness.

Programmatic factors that negatively affect interventions for older homeless persons include limited availability of housing alternatives or in-home services for disabled older adults, agency staff who lack motivation or skills to assist older persons, and an absence of outreach programs that target older adults. Although it is now recognized that most older homeless persons do not suffer from severe mental illness, the closing of mental hospitals (“deinstitutionalization”) has been often cited as playing a critical role in causing homelessness. But evidence suggests that it does not exert such a direct effect. There is usually a time lag between a person’s discharge from a psychiatric hospital and subsequent homelessness, and many mentally ill homeless people have never been hospitalized. Mental illness may indeed contribute to homelessness, especially among older women. But it is also apparent that the over-representation of the mentally ill among homeless persons more accurately reflects systemic factors such as inadequate entitlements and a scarcity of appropriate housing.

Triggers for Homelessness

The research literature has often dichotomized homelessness among older adults as resulting either from a long “slide” accelerated by an accumulation of events or risk factors over time, or from a “critical juncture” in which a crisis compels the person to leave his or her residence. However, many cases involve both: first a cumulative series of events or risk factors, then one final event that triggers true homelessness. Martha Sullivan’s study in New York City found that older women had experienced an average of three major life events or crises over a period of one to five years preceding their homelessness. Specific proximal causes (direct “triggers”) of homelessness among older persons depend largely upon the person’s age when first becoming homeless. In Britain, Maureen Crane drew three conclusions from a study of older homeless people. For those who first became homeless in early adulthood, homelessness was triggered by a disturbed family home, or by discharge from an orphanage or the armed services. For those who first became homeless in midlife, triggers included the death of a parent, marital breakdown, and a drift to less secure transient work and housing. Late-life homelessness often followed the death of a spouse, marital breakdown, retirement, loss of accommodation tied to employment, or the increasing severity of a mental illness.

It has been noted that for women in general, homelessness is apt to be triggered by failures or crises in family life, whereas for men it is more closely linked to occupational failures. While older men commonly have long histories of homelessness, older women are more often driven to it by a crisis in later life.

Intervention Strategies

Older homeless persons are a heterogeneous population. In Britain, for example, Anthony Warnes and Maureen Crane identified seven subtypes based on where they slept, their use of hostels and day centers, and whether they worked, used alcohol, had psychiatric illness, received benefits, moved frequently, or had been rehoused in the past. Such diversity is worth keeping in mind when devising intervention strategies.

Three key points are particularly noteworthy with respect to such strategies. First, because these older homeless are perhaps the most heterogeneous of homeless subgroups—with broad differences in health, cognitive status, and length of homelessness, for example—interventions must be even more individualized than in younger populations. Second, interventions are possible at any point in the model shown in Figure 1: at the distal level (that is, in early and midlife), the proximal level (addressing immediate triggers for homelessness), and subsequent to becoming homeless. Third, in contrast to the self-sufficiency model used for younger persons—that is, moving from transitional supported residential situations to independent living—it may be more profitable to consider various types of permanent supported living arrangements for more vulnerable older persons.

However, unless new statutory interventions are forthcoming, the number of older persons at risk for homelessness will surely increase in tandem with the general population over age fifty. Unfortunately, many individual risk factors—such as previous incarceration, history of disrupted marriages, likelihood to be living alone, lifetime of low-income occupations, and greater use of illicit drugs—are the product of social forces that have left an indelible imprint on the postwar generation.

Options For Progress

Despite these ominous signs, a dramatic increase in aging homeless persons may be forestalled by various statutory and service initiatives such as the following.

Legislation must be passed to improve income supports for suitable housing, especially in geo-graphic areas where relatively low-cost housing is available. In areas where income and employment levels may be higher but affordable housing is scarce, legislation should focus on developing more inexpensive housing.

Policy must address the needs of the fifty-to-sixty-five age group with health and other safety-net supports. Compared with their younger counterparts, they may have difficulty securing employment if they are laid off, they have more physical problems, and they are more apt to experience the death of a spouse and losses in close social ties.

Where legislation exists to provide assistance, benefits must be easily secured. Older persons who are eligible for benefits often do not obtain them, and those who do may not obtain the maximum allowable amounts. Judicial and administrative actions may be needed to enforce existing statutes.

Mentally ill homeless persons often need case managers who can help them secure entitlements and housing and link them to appropriate medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse treatment. Several demonstration projects have shown this to be valuable. Although not specifically targeted to older homeless persons, all of them included persons over age fifty.

Greater emphasis must be placed on preventing homelessness by early identification and help for people at risk. Effective systems of support should enable people to manage in independent or supported housing and should help prevent relinquished tenancies and evictions. Extant laws which may unintentionally foster homelessness should be changed. For example, persons in public housing or who receive federal Section 8 rent subsidies are prohibited from sharing their apartment with non-family members. Thus, if a family member dies or moves away, the remaining person may be unable to pay the rent.

Better reviews of condemned or uninhabitable buildings are needed, to ensure that the eviction of current tenants is not leading to other uses for the properties. Older persons are especially vulnerable to such issues since a disproportionate number live in declining neighborhoods with many dilapidated buildings. Government agencies in charge of formally condemning buildings could be required to institute mechanisms for providing transitional assistance to tenants. “Early warning” systems need to be created to identify vulnerable people who are not coping at home—before rent arrears and other problems accumulate and eviction proceedings commence. In the United States, efforts to prevent homelessness include legal assistance projects to help forestall evictions, cash assistance programs to assist with rent arrears, and direct landlord payments and voucher systems to ensure that tenants can cover their rents.

At the service level, there has been a paucity of programs for homeless and marginally housed older persons. Age-segregated drop-in social centers coupled with outreach programs have been shown to be useful with this population. Unfortunately, while many agencies proclaim an official goal of rehabilitating homeless persons and reintegrating them into conventional society, the bulk of their energies go into providing accommodative services that simply help them survive from day to day.

For extreme cases, help may be provided by a mobile unit of the type developed by Project Help in New York City to involuntarily hospitalize persons. Used judiciously and with awareness of civil rights, such units can assist those elderly homeless who are suffering from moderate, severe, or life-threatening mental disorders.

Finally, advocacy is important. For example, in Boston, the Committee to End Elder Homeless consists of a coalition of public and private agencies working to provide options for this population.

The imminent burgeoning of the aging population will result in a substantial rise in at-risk persons. Prevention of homelessness among older persons will depend primarily on addressing systemic and programmatic factors.

References:

- Cohen, C. I. (1999). Aging and homelessness. The Gerontologist, 39, 5-14.

- Cohen, C. I., Ramirez, M., Teresi, J., Gallagher M., & Sokolovsky, J. (1997). Predictors of becoming redomiciled among older homeless women. The Gerontologist, 37, 67-74.

- Cohen, C. I., & Sokolovsky, J. (1989). Old men of the Bowery: Strategies for survival among the homeless. New York: Guilford Press.

- Cohen, C. I., Sokolovsky, J., & Crain, M. (2001). Aging, homelessness, and the law. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 24, 167-181.

- Crane, M. (1999). Understanding older homeless people. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Hecht, L., & Coyle, B. (2001). Elderly homeless. A comparison of older and younger adult emergency shelter seekers in Bakersfield, California. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 66-79.

- Keigher, S. M. (1991). Housing risks and homelessness among the urban elderly. New York: Haworth Press.

- Sullivan, M. A. (1991). The homeless older woman in context: Alienation, cutoff, and reconnection. Journal of Women and Aging, 3, 3-24.

- Warnes, A., & Crane, M. (2000). Meeting homeless people’s needs. Service development and practice for the older excluded. London: King’s Fund.

See also:

Free essays are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom essay, research paper, or term paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price. UniversalEssays is the best choice for those who seek help in essay writing or research paper writing in any field of study.