This sample Ancient Greece Essay is published for informational purposes only. Free essays and research papers, are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality essay at affordable price please use our custom essay writing service.

Greece is a rugged land at the southeastern corner of the European continent, across the Aegean Sea from Asia Minor (modern Turkey) to the east. To the west, on the other side of the Ionian Sea, is Italy. Southward lies the island of Crete. Farther still, in a southeastward direction across the Mediterranean, is Egypt. In observing the map of Greece, three notable facts are clear. First is its location, close to many great centers of ancient civilization; second is its rough coastline, a series of islands, inlets, and peninsulas; and third is its small size. A little more than 50,000 square miles (129,500 square kilometers), it is about as large as the state of Alabama.

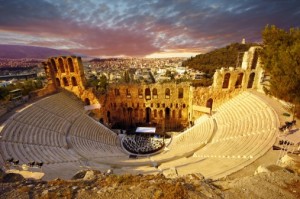

It is hard to imagine a world without Greece because virtually every aspect of modern life owes something to the ancient Greeks. This is particularly so in Western nations such as the United States, where people enjoy the freedoms associated with democracy, a form of government created in Athens some 2,500 years ago. There are all the benefits of science, which only emerged as a discipline with the Greeks, not to mention the arts, from architecture to theater, which would be completely different without the Greek legacy. Even sports owe a huge debt to Greece, where wrestling, track and field, and a number of other athletic events were born. Finally, there is language itself, which is filled with words derived from Greek—athletic, architecture, democracy, theater—and history.

Greek Geography and History

The study of ancient Greece can be rather confusing because of the tiny geographical size of the country, along with the historical importance of so many spots. Thus it is useful to organize the geographical areas of Greece in one’s mind—for instance, by remembering that the focus of Greek history shifted from the south to the north over thousands of years. That history began on the southernmost part of the Greek isles, in Crete, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) off the Greek mainland. Later on, the city-states of the southern mainland would hold center stage; and in the last phase of Greek history, Macedon in the far north dominated the region.

The study of ancient Greece can be rather confusing because of the tiny geographical size of the country, along with the historical importance of so many spots. Thus it is useful to organize the geographical areas of Greece in one’s mind—for instance, by remembering that the focus of Greek history shifted from the south to the north over thousands of years. That history began on the southernmost part of the Greek isles, in Crete, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) off the Greek mainland. Later on, the city-states of the southern mainland would hold center stage; and in the last phase of Greek history, Macedon in the far north dominated the region.

Greece is shaped like the leg of an eagle or some other great bird. Its “thigh” comes down from Macedon in a southeasterly direction, narrowing to a strip of land that eventually reaches a sort of knee—or rather think of the “joint” as an “elbow,” given its angle. Southwest of the “elbow” is an even narrower strip of land, which leads to a giant “claw” at the far southern tip of the Greek mainland. This “claw” is a peninsula called the Peloponnese.

Many of the most important cities of Greek history, including Sparta, Mycenae, and Olympia, were located on the Peloponnese. The upper portion of the Peloponnese, Achaea, included another important city, Corinth. North of Corinth is the Gulf of Corinth, a body of water that forms the western boundary of the “elbow.”

The “elbow,” bounded by the Aegean Sea on the east, contains the region of Attica. The principal city of Attica was Athens, the birthplace of Western civilization. North of Attica, on the upper part of the eagle’s leg, was Boeotia, a region that contained the city of Thebes. To the northwest of Thebes was the important religious center of Delphi.

The “thigh” included a number of important regions: Aetolia, Epirus, and Illyris (modern-day Albania) on the western coast; Thessaly on the eastern coast; and Macedon at the far north.

Beyond Greece to the northeast, where the nation of Bulgaria is now located, was the area of Thrace. Across a narrow sea passageway called the Hellespont was Asia Minor. Northwestern Asia Minor included the city of Troy. The southwestern coast was the region of Ionia, which contained a number of important Greek settlements.

Finally, far away to the west, was an area called Magna Graecia, or “Great Greece.” These were colonies on the Italian peninsula and the island of Sicily south of it, including Sybaris and Syracuse. The term colony, in the context of ancient Greece, has a meaning similar to that used in connection with Phoenicia. The Greek colonies of Italy were important contributors to Greek culture and would play a part in the histories of both Greece and Rome.

The Minoans

At some point during the Neolithic Age, a people called the Minoans settled on Crete. Historians do not know where the Minoans came from, though it is likely they had their origins in Asia Minor. It is less of a mystery why they were drawn to Crete, which has a sunny, pleasant climate. Its hillsides abound with sweet-smelling flowers. The fertile soil is ideal for planting grains and fruit—most notably grapes and olives. From an early point, wine and olive oil became the most significant products of the area. They remain a major part of Mediterranean cuisine.

In about 2000 B.C., the Minoan civilization underwent a sudden upsurge, entering a golden age. For the next five centuries, it would rival the great civilizations of the time: Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and Babylonia around the time of Hammurabi. The Minoans had their own system of writing, which archaeologists refer to as Linear A. However, Linear A has never been deciphered; therefore most of what is known about ancient Crete is the result of archaeological finds.

The center of the Minoan culture appears to have been the Palace of Knossos, the greatest of some thirty Bronze Age sites uncovered by archaeologists. The evidence of Knossos and three other palaces has led scholars to the conclusion that some time around 1700 B.C., Crete experienced a major earthquake or a series of earthquakes. Afterward, Knossos and the other palaces were rebuilt, this time on a larger scale.

It appears that Knossos and the other major centers of Minoan civilization experienced some kind of disaster in about 1450 B.C. As with Teotihuacan in the New World, archaeologists are unsure exactly how Minoan civilization suddenly came to an end, though a number of explanations have been put forward.

Perhaps a tidal wave, the result of a volcanic eruption or earthquake, struck the island and sank part of it. This may in turn have provided the source for the legend of Atlantis, a once-great civilization supposedly submerged beneath the Atlantic Ocean. The legend received a major boost when no less a thinker than the philosopher Plato wrote about it. In fact “Atlantis” was probably a part of Crete in the Mediterranean.

In the A.D. 1960s, archaeologists began finding evidence that a great volcano struck the island of Thera, between Crete and the Greek mainland, some time around 1500 B.C. Again like Teotihuacan, the natural disaster may have been coupled with political upheaval—perhaps a popular revolt spurred on by the government’s inability to deal with the problems, such as homelessness and disruption of normal activities, created by the disaster. It is also quite possible that the earthquake provided an opportunity for invasion by a group who would usher in the next phase of Greek history: the Mycenaeans.

The Mycenaean Age

The Mycenaeans probably came from the Black Sea area starting in about 2800 B.C. Undoubtedly they were part of the Indo-European invasion: their language was an early form of Greek, itself an Indo-European tongue. By 2000 B.C., they had conquered the native peoples of Greece and had settled in the Peloponnese. A warlike people, the Mycenaeans built a Bronze Age civilization that flourished throughout the region beginning in about 1650 B.C.

The Mycenaeans, who had lived in the shadow of the Minoans for a long time, adopted aspects of Minoan civilization. Their language was probably unrelated to that of the Minoans; however, in its written form, they adapted it to the Minoan script, which has been dubbed “Linear B.” Linear B was deciphered in A.D. 1952 by an amateur linguist; similarly, an amateur archaeologist would discover the ruins both of Mycenae, the Mycenaeans’ principal city, and of their ancient rival Troy.

Among the findings of amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann were the Shaft Graves, a series of tunnels where Mycenaean royalty had been buried. The shafts contained enormous wealth in gold jewelry, ornaments, and other objects. Fortunately for the world, this treasure was discovered by a serious historian and not by grave robbers such as those who spoiled the treasures of Egypt and China.

Based on Schliemann’s findings, it appears that the Mycenaeans also imitated the Minoans in the building of great palaces. Mycenae was centered around a fortress called an acropolis, located on a high spot overlooking the town. This type of elevated fortress would become an important feature of Greek cities in the future. Thanks to Schliemann, scholars have some idea of the Mycenaean original.

The Mycenaean acropolis had a huge main gate and, as with Minoan palaces, had a long series of hallways and passages that ultimately led to the great hall or megaron. There the king sat on his throne and oversaw the business of the kingdom. Along the walls were frescoes, paintings applied directly to a wall, showing various scenes.

Also like the Minoans, the Mycenaeans worshiped an earth goddess, but they combined this with worship of sky gods, which formed the basis for the later Olympian religion. The Mycenaeans differed too from the Minoans in their attitude toward foreign affairs. They were at least as interested in waging war as they were in conducting trade. Whereas the Minoans had spread prosperity throughout the region, the Mycenaeans were harsh people who attacked weak cities and formed alliances with strong ones. They did, however, attack at least one strong city: Troy.

The Dark Ages

History is filled with fascinating chains of events, which are like a string of dominoes falling one by one—only, in the case of historical events, the results are much less predictable. The building of the Great Wall of China in the 200s B.C., which displaced nomadic tribes from the region, created a series of shock waves felt all to the way to the gates of Rome some 600 years later. What happened in Greece in the 1100s B.C. was similar, though on a much smaller scale.

From the north, in Macedon, came a group of barbarians who moved into Epirus and Thessaly. The Macedonians would later have an enormous impact on Greek history, but at this early stage, their primary effect was to scatter the Dorians, another barbarian group, from their homeland in about 1140 B.C.

The Dorians in turn swarmed southward, over the strongholds at Mycenae and elsewhere. The Mycenaeans were not the same strong nation that had once taken over from the Minoans. The Dorians, though they may have been uncivilized, had a technological advantage. They had developed iron smelting, and the Mycenaeans, with their Bronze Age weapons, were no match for them. Armed with their superior iron swords, the Dorians swept into the Mycenaean cities, sacking and burning as they went. The Dark Ages had begun.

The Foundations of Greek Culture and Civilization

Though people consider Homer one of the greatest writers of all time, for centuries many believed that he never existed. Rather than a single figure named “Homer,” some suggested, the name had been given to a group of poets who together composed the works attributed to him. But just as Schliemann proved the existence of Troy, scholars came to believe that there really was a poet named Homer. They can say only that he lived some time between 900 and 700 B.C.

Most likely Homer was a wandering poet who earned his living by going to towns and presenting his tales—the “movies” of his day. Often he is depicted as blind; certainly he did not rely on reading and writing for his art, but rather memorized his long stories, which he sang over many nights while strumming upon a harp-like instrument called a lyre. These stories were the Iliad and the Odyssey, fictional accounts of gods, heroes, and their actions during the Trojan War and afterward. They were the central works of Greek literature, and particularly Greek literature as it concerned the conflict with Troy.

More is known about Hesiod, who flourished in about 800 B.C. His most important works were the Theogony and Works and Days. The Theogony tells about the creation of the universe and the origination of the gods. Works and Days includes the story of Prometheus. In writing these epic poems, Hesiod, like Homer, was setting down traditions already established, rather than making up new stories.

These traditions were the Greeks’ mythology, a collection of tales about gods and heroes. Usually mythology is passed down orally. Most Greek myths became a part of literature, either in the works of Homer or Hesiod or in the writings of later Greek poets and dramatists. Eventually they formed the cornerstone of Western literature, along with the Bible. As with the Bible, expressions and stories from the Greek myths are a part of daily life in America and other Western nations. In ancient times, they helped give the Greeks a common culture.

Archaic Greece

Already by the latter part of the Dark Ages, Greece was awakening. For the first time, the peoples of the Greek mainland and isles began to see themselves as one culture if not one nation. They called themselves Hellenes. Words such as Hellenistic describe their civilization.

Part of the Greeks’ awareness of themselves came from contact with other lands. In about 850 B.C., they began trading with other peoples. This led to an increase both in wealth and knowledge. The following century saw the rise of city-states. By 700 B.C., Hellenistic culture had begun to flower. From that point historians date the Archaic Age (ahr-KAY-ik, meaning old) in Greece.

Among the unifying factors of Greek culture were religious and national myths. Throughout the land, people believed in more or less the same gods; shared the same set of myths concerning the Trojan War, including the Iliad and the Odyssey; and admired the same mythic heroes, particularly Heracles. There was also a single Greek language, despite the existence of regional dialects.

Finally, just as the Olmec of Mesoamerica had their ceremonial centers, virtually all Greeks held three sites sacred. At Delphi, there was the Oracle. Off the Aegean coast to the east was the island of Delos (DEE-lohs), legendary birthplace of Apollo and Artemis, which would play a major role in Classical Greece. Thirdly, there was Olympia in the far western Peloponnese, where the peoples of the city-states gathered every four years for a series of contests and religious celebrations called the Olympic Games.

The Formation of City-States

The many factors unifying Greece were significant, since there were plenty of other forces pulling it apart. Except for rare periods, Greece would never be a single nation, but rather a collection of city-states, or cities that also functioned as separate nations. The Greeks called a city-state a polis, from which the English language takes words such as police and politics. The plural of polis was poleis.

At one time there were as many as seven hundred poleis in Greece, though only a few assumed real significance. One of these was Thebes (pronounced like “thieves,” but with a b) in Boeotia, a city much older than most on the Greek mainland. Founded as early as 1500 B.C., Thebes had the same name as an Egyptian city established some five centuries earlier.

On the northeastern corner of the Peloponnese was another important city, Corinth. Founded by the Dorians, it had emerged as an important trading center. Much later, Corinth would figure in the early history of Christianity, with the inclusion of Paul’s two letters to the Corinthians among the books of the New Testament.

Then there were two other cities, that stood above the rest in importance. These two were Athens and Sparta, rivals for leadership of the other Greek city-states. In fact, they were not merely rival cities; they were rival ways of life.

The Birth of Philosophy and Science

Though the architecture of Greece is one of its visible legacies, some of the most significant Greek contributions to the modern world cannot be seen: democracy, for instance, and philosophy. The latter word comes from two Greek roots that together mean “love of knowledge.” Originally, the term was applied to all forms of study. Even today, when a person completes a doctor’s degree, the highest educational level in most disciplines, he or she most often receives a “doctorate of philosophy” degree, which is what the term “PhD” stands for in Latin.

The word philosophy is used in many ways, but in its purest sense it means a search for a general understanding of values and of reality. It is interesting to observe that in the century from 600 to 500 B.C., as Western philosophy was come into existence in Greece, Eastern philosophy had its birth with Confucius and Lao-tzu. However, Eastern and Western approaches to thought are radically different from one another, so much so that they are rarely studied together. The concerns of Confucius and Lao-tzu, after all, were quite different from those of the first Western thinker, who sought to identify the underlying nature of the world.

The conclusion reached by Thales (625?–547? B.C.), who lived in the Ionian city of Miletus, was that “everything is water.” In other words, Thales thought that the whole world is in a fluid state, like water. Thales had first come to fame for predicting a solar eclipse on May 28, 585 B.C.; later he made several advances in the area of geometry. He was the first true scientist: with his statement about water, he was developing the first hypothesis, a Greek word that means a statement subject to scientific testing for truth or falsehood.

Yet he was not talking only about the physical world, as scientists do, but also about what people in a later time would have called the mental or spiritual worlds—the realms of philosophy. In Thales’s time, no one had any idea that there was a distinction between those worlds. Indeed, he was the first in a long line of thinkers (a line that has continued to the present day) concerned not only with philosophy, but also with mathematics and/or science.

Another great philosopher-mathematician was Pythagoras (c. 580-c. 500 B.C.) Born in Samos, an island off the coast of Asia Minor, he settled at the other end of the Greek world, Crotona in southern Italy (then called Magna Graecia). He is most famous for the Pythagorean Theorem, which states that in a triangle with a right angle (i.e., a 90-degree angle), the square of the length of the hypotenuse, or longest side, is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. This was far from his only contribution to thought, however, and though none of his actual writings have survived, the record left by his followers shows that he had far-reaching ideas on everything from music to government.

The lack of surviving writings by Pythagoras is a problem common with many ancient Greek thinkers and writers: only a tiny portion of the plays by Greek dramatists, for instance, survive. Likewise, only fragments remain from Heraclitus (c. 540–c. 480 B.C.) Instead of water, Heraclitus maintained that the world was made of fire—that everything is conflict and change. His most famous statement was: “You cannot step into the same river twice, for other waters are ever flowing on.”

Heraclitus has been compared with the Pythia because he was often so hard to understand. Parmenides (born c. 515), who like several others was a scientist as well as a philosopher, was quite the opposite. He came from Elea in southern Italy. Parmenides introduced the use of logic in philosophy. His thoughts survive primarily in two fragmentary poems contrasting “The Way of Opinion” with “The Way of Truth.” In the latter poem, a goddess states the central idea of Parmenides’ work: “only Being is; not-being cannot be.”

In contrast to Heraclitus, Parmenides saw everything as part of a single, harmonious whole called “Being.” Because everything was part of everything else, in his view, nothing ever changed. His disciple Zeno of Elea (c. 495–c. 430) tried to prove this idea with his famous paradoxes. A paradox occurs when something seems contradictory or opposed to common sense but is in fact correct. Zeno’s paradoxes, however, failed to proved that motion is impossible. Instead, they only proved the flexibility of logic and set off whole new debates. Even at this early stage in the history of philosophy, there were many schools of thought. Disagreement about the nature of the world would only widen as time went on.

The Classical Age

The Classical Age in Greece is one of the most celebrated periods in the history of civilization. There has been no other era quite like it, when so many outstanding figures appeared on the scene at the same time. It was a time when philosophy, literature, sculpture, architecture, politics, and many other fields of human endeavor reached a high point.

No wonder, then, that a period of just 75 years within the approximately 160 years of the Classical Age would come to be known as the Golden Age (479–404 B.C.), the brightest phase of Athens’s history. Even shorter was the brilliant Age of Pericles (c. 495–429 B.C.), who led the city for just three decades.

Not only was the Classical Age brief, but it was marked by war from beginning to end. First, there was a war between the city-states and an enemy from outside, a conflict which united all the Greek peoples under Athens’s leadership. Then, there was a conflict between Athens and Sparta, the Peloponnesian War (431–404 B.C.), which ended in disaster for Athens. Finally, there was the eruption of a new power from the north, the Macedonians, who would sweep over Greece in 338 B.C.

Great Figures of Classical Greece

With all the turmoil that characterized the Classical Age, it may seem odd that the period is considered one of the greatest in history. And yet it was, a time when philosophy and literature flowered alongside science, the arts, and even politics. It was, in fact, the time when history—literally—was born.

Prior to Classical Greece, the writing of history had tended toward one of two extremes. On the one hand, it might be a mixture of myth and fact, exciting enough, but not always reliable, as in the Homeric legends or the Old Testament account of the world’s creation. On the other hand, it could be a mere series of names or facts, as in other parts of the Old Testament or in the annals of the Shang Dynasty kings.

Herodotus (c. 484–c. 425 B.C.) is known as the “Father of History” because he was the first writer to deal with historical events in a systematic way. In his history of the Persian Wars and other writings, he managed to present a compelling narrative, or story, while at least trying (not always very hard) to conform to the facts.

Thucydides (c. 471–401 B.C.) had a much tougher approach to facts, which earned him a reputation as the first critical historian. A critical historian is someone who looks deeply into events rather than simply accepting them at face value. As a commander of a force that went up against Brasidas, he had an eyewitness perspective for the writing of his History of the Peloponnesian War.

Xenophon (c. 431–c. 352 B.C.) had even more military experience, having served in the army of mercenaries hired by Cyrus the Younger to use against his brother Artaxerxes. He wrote a number of works, including Hellenica, a history of Greece following the Peloponnesian War, and several books on a remarkable man he had known and admired. That remarkable man was Socrates (c. 470–399 B.C.), who so greatly expanded the reach of philosophy that those before him are often referred to as the pre-Socratic philosophers.

Greece under Macedonian Rule

In the early 330s B.C., Greece began to experience rumblings from the north from a people beyond its borders who considered themselves heirs to the Grecian heritage, even if the Greeks themselves did not consider them entirely Greek. They seemed to have come out of another time, a world quite removed from the refinements of Athens—a world more like the Greece of myth, when heroes such as Achilles walked the earth.

They were the Macedonians, a hard, warlike nation who, along with the much softer Lydians, considered themselves the descendants of Heracles. They absorbed the culture of Greece. Unlike the Spartans, they recognized that their focus on warfare and survival brought with it certain limitations. They were more like the Persians in their respect and admiration for the cultures of gentler lands they conquered.

The Macedonians had their origins in the distant past, so far back that myth explained them as descending from a son of Zeus called Macedon. (Similarly, the Bible describes the African Kushites as having come from a grandson of Noah named Cush.) They were goatherders, a tribal people whose animals grazed on the slopes of Mount Olympus. In time they became so cut off from the rest of Greece that their dialect could hardly be understood.

The Macedonians’ true history began with Perdiccas (puhr-DIK-uhs), a Greek who came north and took the throne in about 650 B.C., establishing a dynasty that would rule Macedon for more than three centuries. In 510 B.C., his descendant Amyntas I (uh-MIN-tuhs) expanded the kingdom greatly by making an alliance with the Persians. The Persians were on the move in the area, of course, building their empire and soon coming to blows with the Greeks.

Alexander I (r. c. 495–452 B.C.) used Persian help to further strengthen his nation’s power; but unbeknownst to the Persian emperor Xerxes, he was supporting the Greeks fighting the Persian Wars. After the defeat of the Persians in 479 B.C., he helped himself to lands between Macedon and Thrace, but his dream of a Macedonian empire seemed to die with him. Not only were the Greeks of the Golden Age too strong an opponent, but the various tribes of Macedon did not always follow their rulers, and the kings after Alexander were weak. Then in 359 B.C., a king powerful enough to fulfill Alexander’s dream took the throne.

The Reign of Philip II

Philip II (382–336 B.C.) reorganized Macedon, consolidating his power in the court and transporting people from various regions of the country to other parts. It was a strategy employed by the Assyrians to prevent local groups from challenging the central authority. In Philip’s case it gave him a free hand to extend his control far beyond Macedon’s borders.

Philip had invented a new weapon called the pike, a spear some sixteen feet long—a good nine or ten feet longer than the spears of Greek hoplites. Armed with pikes, his army was the most powerful in the region. Between 354 and 339 B.C., he conquered an empire that stretched across the Balkan Peninsula in the southeastern corner of Europe. From Illyria in the west to the Danube River (dan-YOOB) in the east, Philip, having broken the power of the Scythians over the Black Sea region, was king. Then he turned his eyes southward, toward the true prize: Greece.

Philip did not consider himself an outsider conquering a foreign land but a fellow Greek bringing the Greeks together. Therefore he went into Greece, not to make war, but to bring peace (at least, from his perspective). Having gained an alliance with Thessaly, he defeated a huge Greek army and put an end to a war in 346 B.C. that pitted various Greek leagues against one another for control of Delphi. As president of the Pythian Games, an important symbolic position, he called on Athens to join other city-states in what he called the Greek League.

Regardless of how Philip viewed himself, Athenians saw him as a barbarian. Leading the attacks against him was Demosthenes (384–322 B.C.), a famed statesman and orator. Beginning in 351 B.C., Demosthenes made a series of brilliant speeches in which he warned against the Macedonians and their king. In one of these speeches, called the “Philippics,” he said of Philip, “Observe, Athenians, the height to which this fellow’s insolence has soared: … he blusters and talks big … he is always taking in more, everywhere casting his net round us, while we sit idle and do nothing.”

Demosthenes urged the Athenians to join Thebes and other city-states in opposing Philip. The two forces met in battle at Charonea in 338 B.C. The Greeks were no match for Philip’s army, and Charonea marked the end of Greece as an independent force. Soon all the city-states joined the Greek League. Philip prepared to fulfill his ultimate dream of leading a combined Macedonian and Greek force eastward, where they would conquer the Persian Empire. He did not live to see it, however. In 336 B.C., when he was only forty-four years old, Philip was killed by an assassin. Now the crown passed to his son, who would become the greatest conqueror in history.

The Age of Alexander

When he assumed the throne of Macedon, Alexander (356–323 B.C.) was only 20 years old. Within two years, he would embark on a campaign of conquest that would make him ruler, by the age of 30, over almost the entire world as the Greeks knew it. His empire stretched from the Peloponnese to the Indus River and from the mountains of the Hindu Kush to the Cataracts of the Nile. Except for parts of India and Africa, as well as China and of course the Americas, all the civilizations up to that time would come either under direct Macedonian rule or into alliance with Macedon. No leader had ever conquered so much land in so short a time, and no leader would ever do so again.

In those years of conquest from 334 to 326 B.C., Alexander’s empire seemed to promise a newer, brighter age when the nations of the world could join as one, not under Macedonian rule, but in a joint effort which would bring all people together as equals. The Alexandrian Empire made no distinction, or at least little distinction, between racial and ethnic groups: instead, it promoted men on the basis of their ability. In each land he conquered, Alexander and his soldiers took wives and fathered children, not as a way of further subduing the people, but as a way of literally and symbolically uniting themselves with them.

After nearly two years spent consolidating his power in Greece, Alexander marched his troops across the Hellespont in 334 B.C. The first of his army to touch Asian soil, he drove his spear into the ground as a symbol of conquest. He believed himself a descendant of Achilles on his mother’s side, so he made one of the only detours of the long journey ahead, visiting Troy. Further on, he stopped in Gordian, capital of the Phrygians, where he cut the fabled Gordian knot. Then it was on to conquest.

After taking all of Asia Minor, in 333 and 332 B.C., the armies of Alexander occupied Syria, Phoenicia, and Palestine. Alexander’s armies next conquered the most ancient of the world’s lands, one of which the Greeks were in awe: Egypt. There he founded the city of Alexandria. Then he made a big loop into the desert before leaving Africa and marching deeper into Asia. By 331 B.C., Alexander had taken Assyria and reached Babylon. The next major stop was Persepolis, the capital of the Persian Empire, which he took in 330 B.C. With the Persian Empire gone, he ruled the world.

Alexander truly seemed to be as interested in freeing nations as in controlling them. He gave the Armenians their independence. He also expanded his multiracial policies. From the beginning, Alexander’s armies had recruited local troops, but with the full conquest of Persia, this enlistment began in earnest. It was his goal to leave Persia in the control of Persians trained in the Greek language and Greek culture. In addition, he left behind some seventy new towns named Alexandria. This began the spread of Hellenistic culture throughout western Asia.

Over the course of almost six years, from 330 to 324 B.C., Alexander’s armies made a giant loop through what is now Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. If Alexander had had his way, they would have kept on going. In July of 326 B.C., however, just after they crossed the Beas River, his troops refused to continue. It had been eight years since they had seen their families, and even if they turned west immediately, it would be many more years before they reached Greek soil again. Reluctantly, Alexander agreed to turn around and head for home.

He sent one group back by sea, commanding them to explore the coastline as they went, and another by a northerly route. He took a third group through southern Iran, on a miserable desert journey in which the entire army very nearly lost its way. Finally, in the spring of 323 B.C., they returned to Babylon. There Alexander began planning yet another conquest: Arabia. But he took ill from a fever, which was not helped by his recently adopted habit of heavy drinking, not to mention the wearying hardships of the desert journey. Unable to move or speak, he took to his bed, where all his commanders filed by in solemn tribute to the great man who had led them. On June 13, 323 B.C., he died. He was not yet 33 years old.

The Hellenistic Age

In the aftermath of Alexander’s death, his generals quarreled over the spoils of his conquests. None of them were remotely Alexander’s equal in vision; they were merely soldiers, with no ambition to reshape the world. Seleucus (c. 356–281 B.C.) gained control over Persia and Mesopotamia, where an empire under his name would rule for many years. Ptolemy (c. 365–c. 283 B.C.) established a dynasty of even longer standing in Egypt. He and his descendants ruled from 323 until 30 B.C.

As for who would rule Macedon and Greece, that was a much thornier question. Alexander’s successors fought one another over the European homeland. Seleucus and Ptolemy, along with several others, tried to keep Antigonus (382–301 B.C.) from taking over Macedon. Control passed through several hands, with both Seleucus and Antigonus losing their lives in battles over the Macedonian throne.

In 279 B.C., a new and terrifying force appeared in southeastern Europe: the barbaric Celts or Gauls. Antigonus Gonatas (c. 319–239 B.C.), grandson of Antigonus, drove out the Gauls and established a Macedonian dynasty that would last until 167 B.C. He controlled much of Greece through puppet rulers and struggled constantly with Pyrrhus (319–272 B.C.), the king of Epirus, for leadership over the region. Then, in 229 B.C., Rome established a military base in Illyria.

Philip V of Macedon (238–179 B.C.) tried to resist the spread of Roman rule. The conflict between the two powers came to a head in 197 B.C. at Cynocephalae in Thessaly. The troops of Philip, like those of his namesake Philip II, fought using the pike. Military technology had moved on, and the Roman units, with their better swords and armor, devastated Philip’s army. Yet he managed to escape with a few troops, and in the years that followed, he built up his forces.

Philip left his son Perseus (c. 212–c. 165 B.C.) an army of 40,000 men. Still, they were no match for the Romans, who in one battle in 168 B.C. killed some 20,000 Macedonians. They captured Perseus and marched him to Rome, where he died. In 150 B.C. Andriscus, who claimed to be Perseus’s son, tried to lead a revolt against Rome. But the Romans crushed the uprising and in 148 B.C. annexed Macedon. Two years later, they added Greece to their empire.

Greece and Rome

In the Middle Ages, when civilization all but disappeared from Europe, the Arab world would preserve Greek culture and philosophy, particularly that of Aristotle. Farther west, the Byzantine Empire, which grew out of the Roman Empire’s eastern branch in Greece, would maintain a very formal, strict, and static version of civilized learning while Western Europe faded into darkness.

Just as it is impossible to imagine the world without Greece, so it is impossible to fully appreciate the Hellenic impact on civilization without seeing its influence on the last great society of the ancient world: Rome. As Greece was dying out, preparing to pass the torch to the Romans, two new schools of philosophy arose in Athens, Stoicism and Epicureanism. Between them, these two views of the world reflected what was to come for Rome.

The Stoics placed a premium on dignity, bravery, and self-control. So, too, did the early Romans. Indeed, one of their rulers would rank among the greatest Stoic philosophers. The Epicureans originally taught enjoyment of life’s simple joys, but in time this became corrupted. The word epicurean in modern usage means someone who lives for pleasure. Nothing could better describe the later Romans who helped bring about the fall of their empire and the end of civilization in Western Europe for many years.

But before it could fall, Rome had to rise. In its time Rome became a more splendid empire than any that preceded it. Its realm was larger than Alexander’s, and it held it for much longer. During that time, the Romans—the greatest Hellenistic kingdom of all—deepened and widened the influence of the Greeks. Thanks to Rome, Greece would never die.

Bibliography:

- Barber, Richard W. A Companion to World Mythology. Illustrated by Pauline Baynes. New York: Delacorte Press, 1979.

- Bardi, Piero. The Atlas of the Classical World: Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Illustrations by Matteo Chesi, et al. New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1997, pp. 8-33.

- Bowra, C. M. Classical Greece. New York: Time-Life Books, 1965.

- Brumbaugh, Robert S. The Philosophers of Greece. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1981.

- Bulfinch, Thomas. Bulfinch’s Mythology of Greece and Rome with Eastern and Norse Legends. New York: Collier Books, 1967.

- Burrell, Roy. Oxford First Ancient History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, pp. 96-205.

- Chelepi, Chris. Growing Up in Ancient Greece. Illustrated by Chris Molan. Mahwah, NJ: Troll Associates, 1994.

- Harris, Nathaniel. Alexander the Great and the Greeks. Illustrated by Gerry Wood. New York: Bookwright Press, 1986.

- Lyle, Garry. Let’s Visit Greece. Bridgeport, CT: Burke, 1985.

- Martell, Hazel Mary. The Kingfisher Book of the Ancient World. New York: Kingfisher, 1995, pp. 62-75.

- Nardo, Don. Life in Ancient Greece. San Diego, CA: Lucent Books, 1996.

- Priestley, J. B. The Wonderful World of the Theatre. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969.

- Rutland, Jonathan. An Ancient Greek Town. Edited by Adrian Sington, illustrations by Bill Stallion, et al. London: Kingfisher Books, 1986.

- Tallow, Peter. The Olympics. New York: Bookwright Press, 1988.

- Warren, Peter. The Aegean Civilizations: From Ancient Crete to Mycenae. Oxford, England: Phaidon, 1989.

See also:

Free essays are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom essay, research paper, or term paper and get your high quality paper at affordable price. UniversalEssays is the best choice for those who seek help in essay writing or research paper writing in any field of study.